Aubade

By Chinaza James-Ibe

Pa is seated on a kitchen stool, peeling roasted yam with the same concentration as a nurse cleaning a wound. The darkness has been diluted by light, and if you squint harder you can see it receding, tucking its dress between its thighs, and fleeing in a bride-like manner. Mm. Asides the grok grok of the hornbill, and the solemn shuffling of feet outside our compound, everywhere is still. Dawn is the colour of Pami, and each morning, I imagine chugging it until my belly is filled with all the world's light.

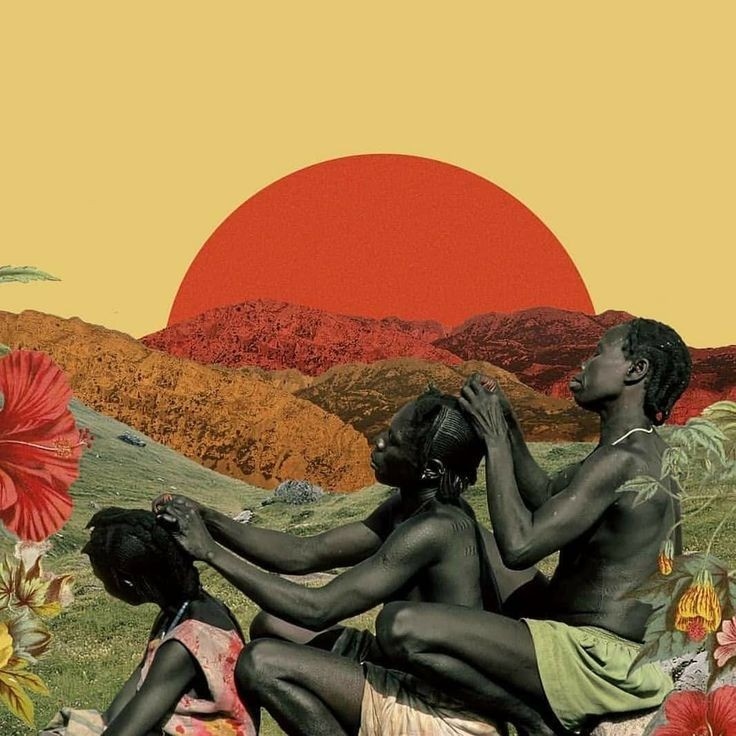

The silence does not last for long, it is Sunday, and a while after the feet have stopped shuffling, we can hear the metal clanging of the wheel-bell. Then the cries of the village choir follow, Enwerem aṅụrị, oge m nụrụ ka ha n’ekwu si, “k’anyi jee n'ụlọ Chụkwụ…” It never matters to me that we are never part of this ritual, because in our own way, we let it govern us. Pa is peeling our yam like it is a prayer. Ma is heating up the oil and slicing an onion bulb into it. On a normal day she would have whistled as she stirred but today, she is silent. Nmuoto’s sleepy steps are dance moves, if I could go into her mind, I can tell that I would find her singing too. She is singing just like me.

This is our prayer—this gentle mutual silence. We move like we are tethered together by a spirit rope. Before Pa can call her and murder the silence, Nmuoto is already by his side with a bowl in which he cuts up the yam into smaller slices. Before Ma can even turn, I am by her side with the blunted Milo tin in which she pours the hot oil. When it scalds my palms, an ‘amen’ which I have borrowed from the church flutters to the bottom of my soul and nestles there. We form a triangle on the bare earth, and everyone is beaming because it is a blessing to be alive. We dip our pieces of yam into oil. We watch our teeth go red, and then yellow; we know that our sacrifice has been accepted.

Today, I imagine spearing the silence with my words. I imagine asking Pa why we don't go to church like all the normal people. In this illusion, Pa has the sun in his mouth instead of a piece of yam. He is laughing and laughing like the excessive light has done nothing but tickle him. Then he stops and gets serious like he always does before he says something wise. Rubbing his belly, he says that family is the only god that he has ever known. This is prayer, he says. This is the only way to feel blessed. Everything could be summed up to a single I love you. But I don't ask any of these questions because I don't really want to know. At the bottom of my soul lies not only an Amen, but contentment.

Somehow, just somehow, I know that even if we don't eat again till it is late in the night and the moon is so bright like a half piece of yam waiting to be tainted; even if we're all weary at the end; even if the children at school call me and Nmuoto the dirty children of pagans; even if at times I get so hurt that I plan to run away one Sunday and fill myself with hymns instead of yam, I know that at the end this is what having a god should feel like. Like choking on smoke on a Sunday morning while Ma heats the oil. Like watching Nmuoto dance. Like listening to hymns from afar and knowing the refrains by heart. Like laughing and laughing when Pa carves his piece of roasted yam into a headless man. Like standing, opening your mouth, and drinking the sky. Like going to bed without even saying a word of prayer but knowing by the warmth all around you that all you could ever pray for has been answered.