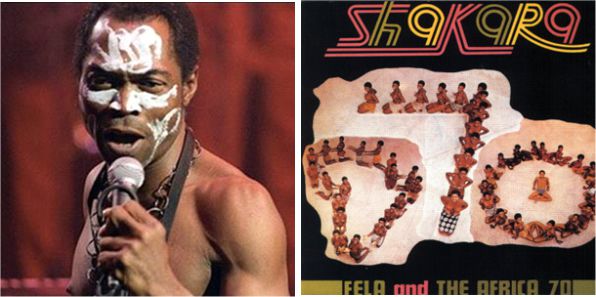

The Living Legacy of Fela’s Shakara

A Look at Fela’s Shakara on its 50th anniversary by Michelle Mojisola Savage

When Fela Anikulapo-Kuti released Shakara in 1972, little did he know how influential it would become. The two-tracked album defined a musical era and birthed another. In fact, ‘shakara’ became part of the West African pidgin lexicon. It was an album like no other.

Fifty years later, to better understand the influence of Shakara in the lives of ordinary Nigerians, I hit the streets. Well, I just took my portable speaker to a group of old men on my street who played draughts and had strong opinions about everything.

If you call am woman, African woman, no go gree

She go say, she go say, “I be lady oh.”

These are the famous lyrics of ‘Lady,’ the first track on the album. As the music flowed from my speaker, I saw these men transform into dancing machines. The oldest one, whose limbs would not allow such energetic movements, spoke of his memories of the song. “When I used to fight with my wife, I would just slip the song into our arguments; ‘She go say im equal to man. She go say im get power like man.’” Immediately, his backup singers drowned his voice. I did not ask if they thought the song was misogynistic. One did not ask such questions from men like them.

The album moved to its second track - Shakara (Oloje). Initially, I skipped the song to Fela’s intro but was quickly reprimanded. “Take it back,” they ordered. So, I sat through exactly 6:27 minutes of instrumentals. With their varying degrees of horrible voices, they sang along like men who remembered the naughty vices of their youth while displaying inferior imitations of Fela’s dance moves. I left their midst during their performance, for I had heard and seen what mattered - the spirit that Shakara invoked.

Click the image to listen to ‘Shakara’.

Back in my room, as I immersed myself in the album, trying to invoke the spirit that gave new life to those old men, I understood what Fela stated during an interview, which was included in Hank Borowitz’s ‘Noise of the World’.

“Music is supposed to have an effect. If you’re playing music and people don’t feel something, you’re not doing shit. That’s what African music is about. When you hear something, you move. I want to move people to dance but also think.”

Shakara was released after Fela experienced his first international success with Chop ‘n’ Quench and Open & Close. Eager to rebrand himself, he changed the name of his band and took over the club of the Empire Hotel in Lagos, renamed African shrine. With his new identity came Shakara, to light the match of his renaissance. The album projected him as not only a political critic but also a talented entertainer. His adoption of pidgin also contributed to its immense success, as his audience was extended beyond Yoruba natives, making him understandable to Anglophone Africans, Europeans, and Americans.

Finally, after listening to the album again, I understood that ‘Lady’ was not Fela’s misogynistic contribution to the war of the sexes, but his anger towards the fast way post-colonial Africans were adopting European norms to the detriment of African culture. Shakara (Oloje), on the other hand, was his light-hearted ridicule of pretentious people. The track is also credited with the popularity of ‘Shakara’, the most prominent of a collection of words popularized by the Afrobeat King.

To Afrobeat, Shakara is everything. Its release was perhaps, the beginning of that musical era. The album’s orchestral arrangements and call-and-response vocals are the backbones of 21st-century Afrobeats. Those features were especially emulated in ‘Jaiye Jaiye’, a 2014 collaboration between Wizkid and Femi Kuti - Fela’s son. To the old men on my street, Shakara helped them to relive their youth. Fifty years from now, they would not be alive to retell its stories. It might not be remembered by Gen Zs, most of whom prefer fast songs with little meaning. But as long as Afrobeats remains, Shakara would live on as the Adam of the genre.