The ancient Kano City Walls encircled medieval Kano City. They were military fortifications for the defence and protection of its citizens. Ingress and egress of people were through gates in the walls, which Sarkin Kofars monitored. In 1903, the walls held off British forces for some time during the Battle of Kano before the city was captured. Dalla hill, Kurmi market, and the emir’s palace, each a significant cultural site of its own, are within the walls.

History

The ancient Kano city walls were built around the civilization and commercial hub of old Kano. Started in 1095 by Sarki Gijimasu, the third, they were completed in the 14th century under Sarki Usman Zamnagawa Dan Shekarau. In the 16th century, however, the walls were reconstructed to their modern-day state and design, although sizable portions are now in ruins.

Location and Structure

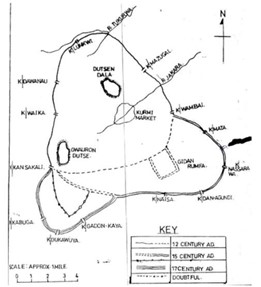

Map of the walls and gates. Picture credit Bayero University

The walls are in Kano, Kano State. They enclose Dalla hill, where the city’s first inhabitants settled, Kurmi market, a commercial centre and hub of the Trans-Sahara trade, and the emir’s palace, the seat of political power. After British forces sacked Kano city in 1903, Sir Sir Frederick Lugard reported the walls to be ‘30 to 50 feet in height, 40 feet thick at the base, pierced by 13 gates, and a length of 11 miles.’ They are made of laterite and styled after North African Mahgrehbi's architecture. Two more gates, Sabuwar Kofa and Kofar Fomfa, were built after the British seized the city. The gates are named: Kofar Na’isa, Kofar Nasarawa, Kofar Wambai, Kofar Waika, Kofar Kansakali, Kofar Gadankaya, Kofar Dukawiya, Kofar Ruwa, Sabuwar Kofa, Kofar Kabuga, Kofar Dan Agundi, Kofar Dawanau, Kofar Mata, Kofar Mazuga, and Kofar Fomfa.

Of the fifteen gates, only three have been reconstructed with laterite in the style of the ancient walls; the rest are of concrete in the manner of modern times. None of the gates have their original iron doors, although three of these doors are in the Gidan Makama Museum, Kano.

Picture credit Nigeria Property Forum

Relevance

The ancient city walls of Kano have historically been regarded as "the most impressive monument in West Africa," Lugard observed in his 1903 report that "the extent and formidable nature of the fortifications surpassed the best-informed anticipations of our officers. Needless to say, I have never seen or even imagined anything like it in Africa.''

The walls are why Kano could fend off external aggression and retain a dominant position as a thriving city-state evolving into the metropolis it is today. They point to the existence of a medieval African civilisation that was advanced. They were named a national monument in 1959 and included on UNESCO’s Tentative list in 2007.

Preservation

In 1903 Lugard referred to the walls as a feature he had never seen or even imagined anything like in Africa. In 1959 they were named a national monument and, in 2007, included on UNESCO’s Tentative list. Yet a 2017, survey that investigated the state of the walls showed that out of 27,412 metres measured, 3,772 were poorly preserved, 12,177 fairly preserved, 789 moderately preserved and 1067 not preserved. Before independence, Sarkin Kofars, district officers, and ward heads protected the walls.

Once they became a national monument, responsibility for their maintenance and protection moved from the Emir of Kano to the government. Since then, very little has been done to continue to safeguard the walls from destruction. The government has been accused of not only shirking its responsibility to maintain and protect them but of allotting land around them to political allies who encroach on the walls with buildings and farms.

The walls are a source of the raw material used for making mud blocks for building houses. The economic benefit derived from the sale of the sand excavated from portions of the wall makes that activity challenging to stop despite its being against the law. Up to 40 to 50 donkey loads of sand so excavated are said to be removed from the walls daily, while it is claimed that as much as 108,000 mud blocks are produced yearly.

There is little to no urban planning to deal with the growth of Kano city. The land very close to the walls is allotted or sold for the construction of houses or farming in violation of the 30-metre legally required distance between the walls and buildings. Ignorance of the people regarding the cultural and historical value of the walls and the laws governing construction around the walls results in their being built over, and their gates are torn down to widen roads.

Recent severe flooding experienced in the city is blamed on the destruction of the walls. Environmental changes, pollution, erosion, rainfall, and human waste threaten the walls’ stability, bringing portions down.

Nonetheless, the walls have been described as ‘an intriguing testimony of African indigenous use of its architecture’ and ‘a magnificent work of military engineering’. A monument almost a thousand years old embodies a history that should be preserved. The preservation is essential to giving the indigenous people of Kano a sense of place, identity, evolution, ownership, and community.

Reconstructed Sabuwar Kofa. Picture credit Al Jazeera

Since the 2007 inclusion on UNESCO’s Tentative list, there has not been sufficient preservation and curtailing of further destruction to progress the status of the walls to a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Effective preservation will require the reconstruction of fallen sections and the protection of existing portions. To achieve this, adequate funding and monitoring are needed. €58,000 given by Germany has allowed some work to be done, though much more is required. Teams from the Gidan Makama Museum patrol what is left of the original walls to prevent further degradation, and it has been suggested that the emirate council should use its influence and authority to organize communal activities to renovate the walls and create awareness amongst indigenes of their historical, cultural and economic value.

Crumbling remains of the walls. Picture credit Semantic Scholar

Tourism

Kano city has several tourist attractions, such as Dalla hill, Kurmi market, the emir’s palace and the Gidan Makama Museum. Tourism is, therefore, a recognised aspect of the city’s economic growth. Given their historical significance, the ancient walls and their gates are of interest to visitors. If well-preserved and managed through strategic government policies, they could become one of Africa's global landmarks and boost national economic growth through tourism and the attraction of investors.