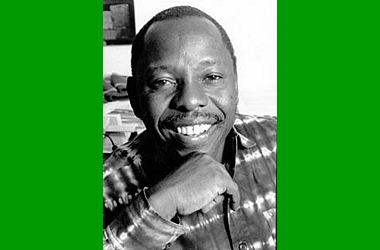

Ken Saro Wiwa (born Kenule Beeson Tsaro-Wiwa) was an author, television producer, environmental activist and the first Nigerian to win the Right Livelihood Award and the Goldman Environmental Prize. He was a member of the Ogoni people, an ethnic minority in Nigeria whose homeland in the Niger Delta has been targeted for crude oil extraction since the 1950s and which has suffered severe environmental damage as a result.

Early Life

Ken Saro-Wiwa was born on October 10, 1941 in Bori, Rivers State. His father, Jim Beeson Wiwa, was an Ogoni chieftain. His parents doted on him because he was, for the first seven years of his life, their only child. He proved himself an excellent student, attending secondary school at Government College Umuahia. Upon completing secondary school, he obtained a scholarship to study English at the University of Ibadan, graduating in 1965. After his graduation, he taught at Government College Umuahia and at Stella Maris College in Port Harcourt. He also briefly worked as a teaching assistant at the University of Lagos before joining the federal forces in the civil war of the late 1960s. He worked as a government administrator until 1973 when he left to concentrate on his literary career. He married Nene Saro-Wiwa in 1967 and they had five children: three sons and two daughters.

Literary Career

Saro-Wiwa was a prolific writer. Through his literary work, he became increasingly involved in activities which brought national and international attention to the campaign of the Ogoni people. Most of his books were published by his publishing company, Saros. As a writer, he first achieved fame with the radio play The Transistor Radio, which was broadcast as part of the BBC African Theatre series in 1972. His first novels, Songs in a Time of War and Sozaboy: A Novel in Rotten English (his best-known book) were published in 1985. He was also a successful television producer. He reached his largest audience with Basi and Company, a comedic television series set in Lagos that ran for more than 150 episodes in the 1980s with an estimated audience of 30 million Nigerians. The series was cancelled by the military dictatorship in 1992 but several of its scripts were adapted into children's books.

He was also a journalist and wrote poetry and children’s stories. He published political columns in the Vanguard newspaper and from 1989, he wrote the Similla column for a local Ogoni Sunday newspaper until his death. Saro-Wiwa documented his experiences during the Nigerian civil war in his diaries On a Darkling Plain: An Account of the Nigerian Civil War (1989). In the satirical Africa Kills Her Sun (1989), Saro-Wiwa foreshadowed his own execution through his critique of the corruption and graft in Nigerian society (and in Africa as a whole).

At the height of his career, Saro-Wiwa wrote and published seven books in one year. However, his success was overshadowed by a family tragedy: the death of his son, an Eton College student, during a rugby game. His other works include Tambari(1973); Mr. B. (1987); Prisoners of Jebs (1988); Adaku and Other Stories (1989); Four Farcical Plays (1989); Nigeria, The Brink of Disaster (1991); A Forest of Flowers: Short Stories (1995); and A Month and a Day: A Detention Diary (1995).

Government Service and Later Years

Saro-Wiwa took up a government post as the Civilian Administrator for the port city of Bonny in the Niger Delta in November 1967 and during the Nigerian Civil War, he was a strong supporter of the federal cause against the Biafrans. In the early 1970s, he served as the Regional Commissioner for Education in the Rivers State cabinet, but was dismissed in 1973 because of his support for Ogoni autonomy. In the late 1970s, he established a number of successful business ventures in retail and real estate.

In 1986, he was appointed director of the Nigeria Newsprint Manufacturing Company. His intellectual work was interrupted in 1987 when he re-entered the political scene, having been appointed executive director of the National Directorate for Social Mobilisation by General Ibrahim Babangida to aid the country's transition to democracy. Saro-Wiwa soon resigned because he felt Babangida's plans for a return to democracy were disingenuous. Saro-Wiwa's sentiments were proven correct in the coming years as Babangida failed to relinquish power.

Activism

In 1990, Saro-Wiwa began devoting most of his time to human rights and environmental causes, particularly in his native Ogoniland. He was one of the first members of the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP), which advocated for the rights of the Ogoni people. He was initially the group’s spokesperson and eventually became its president. The Ogoni Bill of Rights, written by MOSOP, set out the movement's demands, including increased autonomy for the Ogoni people, a fair share of the proceeds of oil extraction and the remediation of the environmental damage to the Ogoni's lands. In particular, MOSOP struggled against the degradation of Ogoniland by the Shell Oil Company.

In mid-1992, he expanded MOSOP's reach internationally, focusing particularly on Britain, where Shell had one of its headquarters. He criticised the destructive impact of the oil industry - the main source of Nigeria’s national revenue - on the Niger Delta region and demanded a greater compensatory share of oil profits for the Ogoni.

He was also an outspoken critic of the Nigerian government, which he viewed as reluctant to enforce environmental regulations on the foreign petroleum companies operating in the area. As a result of mounting protests, Shell suspended operations in Ogoniland in 1993.

From 1993 to 1995, he was the Vice Chairman of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organisation (UNPO) General Assembly, an international organisation which represents indigenous peoples, minorities, and unrecognised or occupied territories who have come together to protect and promote their human and cultural rights, to preserve their environments and to find nonviolent solutions to the conflicts which affect them.

In January 1993, MOSOP organised peaceful marches of around 300,000 people – more than half of the Ogoni population – through four key places, drawing international attention to his people's plight. In the same year, the Nigerian military government occupied the region.

Arrest and Execution

Between 1992 and June 1993, Saro-Wiwa was imprisoned on several different occasions for months without trial by the Nigerian government. On May 21, 1994 four Ogoni chiefs (all of whom were on the conservative side of a schism within MOSOP over strategy) were brutally murdered. Saro-Wiwa had been denied entry to Ogoniland on the day of the murders, but he was arrested and accused of complicity in the murders. He denied the charges, but was imprisoned for over a year before being found guilty and sentenced to death by a specially convened tribunal alongside other eight MOSOP leaders: Saturday Dobee, Nordu Eawo, Daniel Gbooko, Paul Levera, Felix Nuate, Baribor Bera, Barinem Kiobel and John Kpuine.

Nearly all the defendants' lawyers resigned in protest at the trial's rigging by the Abacha regime. The resignations, however, left the defendants to their own means against the tribunal, which continued to bring witnesses to testify against Saro-Wiwa and his peers, many of whom later admitted that they had been bribed and offered jobs with Shell by the Nigerian government to support the criminal allegations.

On November 10, 1995 Saro-Wiwa and the eight other MOSOP leaders (known as the "Ogoni Nine") were executed by hanging at the hands of military personnel. Saro-Wiwa was the last to be hanged and so was forced to watch the death of his colleagues. Information on the circumstances of his death is unclear, but it is generally agreed that multiple attempts were required before he was hanged.

His death provoked international outrage and the immediate suspension of Nigeria from the Commonwealth of Nations, as well as the recalling of many foreign diplomats from the country.

Honours, Awards and Legacy

Saro-Wiwa’s trial was widely criticised by human rights organisations. He received the Right Livelihood Award in 1994 for his courage as well as the Goldman Environmental Prize in 1995.

A memorial to Saro-Wiwa was unveiled in London on November 10, 2006. It consists of a sculpture in the form of a bus and was created by Nigerian-born artist Sokari Douglas Camp. It toured the UK the following year.

Saro Wiwa's trial and execution were sources of inspiration for Beverley Naidoo's 2000 novel The Other Side of Truth as well asEclipse (2009) by Richard North Patterson. Saro-Wiwa’s biography, In the Shadow of a Saint, was written by his son, journalist Ken Wiwa. One daughter, Zina, is also a filmmaker and journalist and her twin sister Noo is a writer.

Despite his death, MOSOP has continued to pursue its initial objectives: the protection of the environment of the Ogoni; social, economic and physical development for the region and the protection of Ogoni cultural rights and practices. In 2009, they agitated for the creation of a Bori State during the review of the 1999 Constitution in Port Harcourt. Till date, the organisation has remained the voice of the Ogoni people

Societies and Organisations

He was a member of many organisations and societies, including the Anti-Slavery Society for the Protection of Human Rights; Phi Beta Sigma fraternity (Alpha Chapter and Mu Chapter); the Royal Economic Society; the Royal Anthropological Institute; the British Association for the Advancement of Science; the American Society of International Law; the American Anthropological and Political Science Associations; the American Ethnological Society; the Amateur Athletic Association of Nigeria; the Nigerian Olympic Committee and the British Empire and Commonwealth Games Association.

Sources