On Protecting the Homestead Pumpkin: On Okot p’Bitek’s Song of Lawino

By Chinaza James-Ibe

On Protecting the Homestead Pumpkin: On Okot p’Bitek’s Song of Lawino

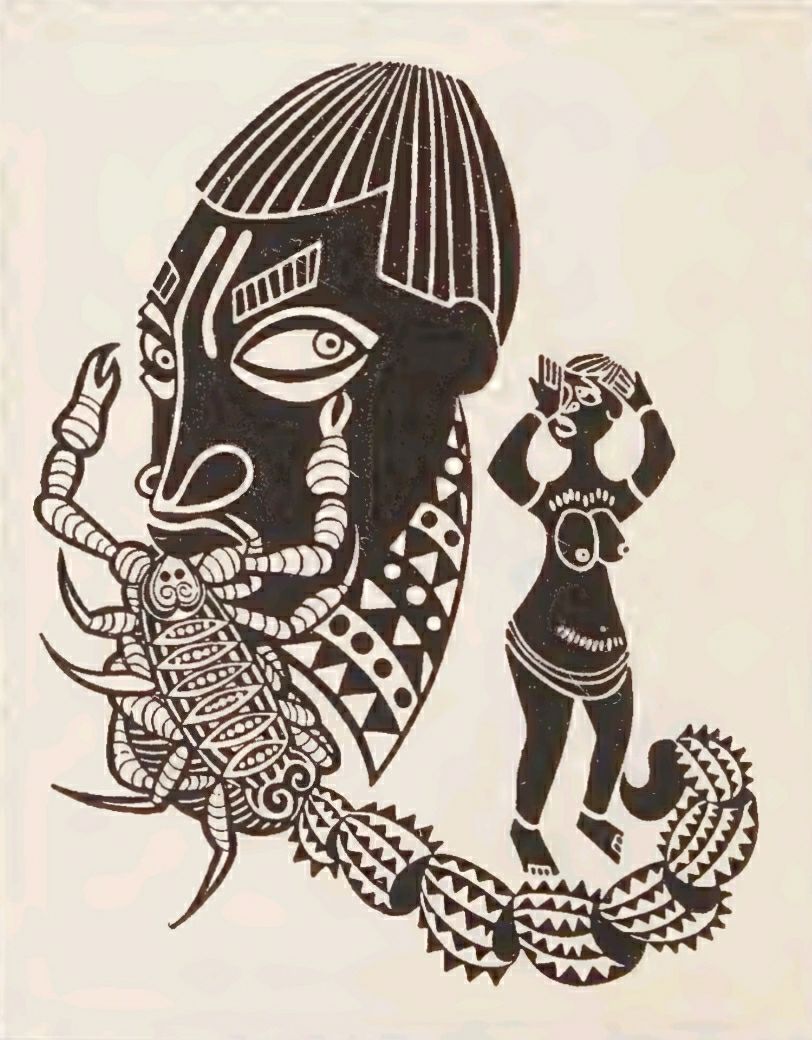

Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned—William Congreve

To read Okot p’Bitek’s Song of Lawino is to sit patiently on a low kitchen stool, beside a corn-roasting hearth; listening to the agitated and long-winded laments of a heavily wronged wife. Lawino’s lament is like the persistent cry of Luke 18’s widow—it commands the ear to listen, and the reader to sympathize. Not only does it command the ear, it equally entices the wit with bold and angry humour; and the senses with imagery so vivid and unhinged that it is difficult to look away. To read Song of Lawino is to discover the mastery and eccentricity with which p’Bitek parallels the tribulations of loquacious Lawino to the ailments of a nation heavy with the gravity of imperial advent. The rehashing of the colonial struggle and the identity crises paired with it is often done from a phallocentric perspective, making Lawino’s lament and critical (often irked) eye a fresh rendering of the colonial experience.

Central to this epic poem is a myriad of nativistic images (from the simsim to the yonno lily). In postcolonial theory, nativism describes the political and cultural efforts by colonized peoples to reclaim and reassert the value of their own traditions and identities, often in opposition to the cultural dominance imposed by the colonizers. It is a call for authenticity and identity—a notion that Lawino reiterates in her lament over the cultural demise of her Western-educated husband, Ocol, whose convoluted actions lay at the apex of the poem’s concerns. Lawino, against Ocol’s supposed intentions, contends for the preservation of Acoli culture. She reprimands: “Listen, my husband,/You are the son of a Chief./The pumpkin in the old homestead/ Must not be uprooted!” Here, “homestead” becomes a synecdoche for a nation, and the “pumpkin” its fruit and its landmark. p’Bitek’s wielding of Lawino pulsates between a culturally wise woman who is content with the font of her cultural idiosyncrasies, and a woman made brazen by scorn. On some occasions, Lawino is rendering calculated advice:

“Listen Ocol, my old friend,

The ways of your ancestors

Are good, Their customs are solid

And not hollow

They are not thin, not easily breakable

They cannot be blown away

By the winds

Because their roots reach deep into the soil.”

And on some other occasions, Lawino is insultingly descriptive:

“You kiss her on the cheek

As white people do,

You kiss her open-sore lips

As white people do,

You suck slimy saliva

From each other’s mouths

As white people do.”

However, Lawino never loses sight of her nativist agenda. She is more appalled by the indigenes’ ready relinquishment of native cultural values for foreign culture, and at the same time, acknowledges that she is ignorant of the alien culture. Lawino advocates the same decolonization of the mind as Frantz Fanon and critiques the same mimicry of the occident diagnosed by postcolonial scholar, Homi Bhabha. The Orient (native) is assimilated into believing that the Occident’s (West) culture is a perfection worthy of aspiration, and in the inherent savagery of indigenous customs, p’Bitek writes: “My husband laughs at me/ Because I cannot dance white men’s dances; /He despises Acoli dances/ He nurses stupid ideas/ That the dances of his/ People Are sinful.”

In discussing the clashing cultures, a formulaic pattern in diction is evident in Lawino’s rendition, whereby Western inclinations are juxtaposed with dereliction and decay, for example, “Vomit and urine flow by/ And on the walls /They clean their anus;” and Acoli culture with vitality and fertility: “When Ocol was wooing me/ My breasts were erect./And they shook/ As I walked briskly,/ And as I walked I threw my long neck /This way and that way/ Like the flower of the yonno lily/ Waving in a gentle breeze.” With Lawino as a medium of social critique, p’Bitek proceeds to comment on the Independence struggle, highlighting the onslaught of corruption, belligerence, and disunification of the natives as a result of political party affinities.

One must notice that little or nothing is addressed to the Whiteman; Lawino’s lament is a call for the reinstitution of Acoli’s beauty by Acoli, and for Acoli.

Ultimately, Song of Lawino transcends a mere domestic quarrel. Through Lawino’s passionate and poignant lament, p’Bitek masterfully critiques the insidious effects of colonialism on African identity and culture. Lawino, with her unwavering defence of Acoli traditions and her scathing indictment of Western cultural influences, becomes a powerful symbol of resistance, reiterating till the very end: “Let no one uproot the Pumpkin.”